The much debated topic of Crossrail was discussed in a panel at RIBA on Monday as part of LFA 2016. The £14.8 billion project is currently Europe’s largest infrastructure project. This time, the focus was not around fears and controversies over its funding framework, the lack of assessment of the noise and pollution caused by the line, nor its impact on listed buildings in Central London areas, but rather on the integration of art, architecture and infrastructure via the newly established Culture Line project.

Chaired by Eleanor Pinfield, Head of Art on the Underground, the discussion brought together a mix of voices including; Harbinder Birdi, Partner, Hawkins/Brown, Kathrin Hersel, Development Director, Almacantar, Richard Wright, Artist (Tottenham Court Road, eastern ticket hall) and Christina Andersen, Crossrail Art Programme Manager.

The Culture Line is Crossrail’s attempt to bring art to the public space of London Underground through a programme of large-scale artworks in central London underground stations. The works are delivered in collaboration with leading art galleries (Gagosian in Tottenham Court Road, Lisson Gallery in Paddington and White Cube in Bond Street). The Crossrail Art Foundation, a registered charity founded by Crossrail in partnership with The City of London Corporation, is in the process of inviting artists to submit proposals for these stations. At Tottenham Court Road the artists Daniel Buren, Richard Wright and Douglas Gordon have been appointed to create site specific artworks.

It was an interesting insight into The Culture Line project, and encouraging to hear that Crossrail is working collaboratively with artists to create meaningful experiences for passengers using the line.

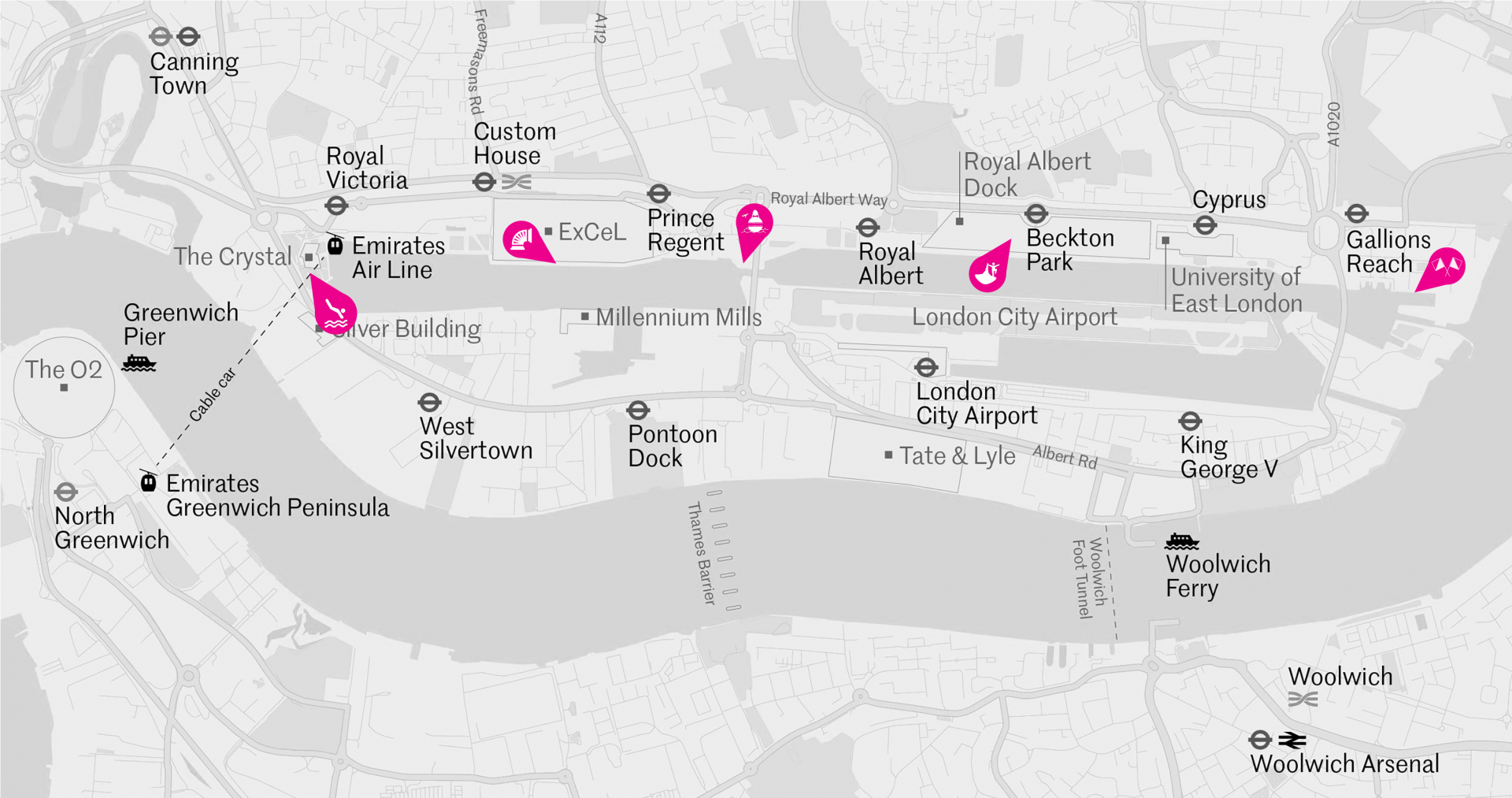

Crossrail is building a new railway for London and the South East, running from Reading and Heathrow in the west, through 42km of new tunnels under London to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east. But while a lot of money and attention is being spent on the Central London ‘underground’ stations, it is easy to overlook that those travelling on the line will spend a considerable amount of time on the surface. An audience member rightly asks whether “there is any ambition to roll out the art programme to those East and West areas on the periphery of the line?” This is a different type of space that could offer an interesting, alterative canvas for artists to work from. In an attempt to reassure, Hersel comments that it is definitely not out of the question, but for now the Central London stations are the priority as this is where they have secured funding. To stretch the programme out to the likes Maidenhead and Romford would require another fundraising stream – so I won’t be holding my breath!

Rather disappointingly the discussion did not reflect on how The Culture Line programme will address the social aspirations, cultural interests and concerns of real communities in those areas.

A woman questioned the medium of artworks being commissioned. As a social space, movement light and sound are at the heart of all of our travels on the underground and so it seems odd that so far all the works being commissioned are monumental, static sculptures and murals. Art on the Underground are increasingly engaging with experimental interdisciplinary practices, commissioning the likes of Benedict Drew and his video artwork de re touch and Matt Roger’s on a free set of audio samples taken from the Victoria Line. Pinfield acknowledges that live art and new media has the power to positively transform our experience on the underground. Whether Crossrail will accommodate this type of work seems unlikely, as Anderson reveals the intention was to commission “integrated artworks that have more permanence”.

We learn that by 2018 Crossrail aims for 7 stations to have major artworks installed in all different shapes and sizes for the future Elizabeth line passengers to enjoy. Eduardo Paolozzi’s mosaic at Tottenham Court Road is continually referenced by the panel as a timeless emblem of public art successfully engaging infrastructure. With Buren, Gordon and Wright now set to follow suit, you are left wondering whether any of these works will be produced by women? Although improving, today around 10% of public art in Central London is created by women – a displeasing figure to say the least. Crossrail has real opportunity here to address this.

There has undeniably been a significant amount of effort on producing the “largest collaborative art commissioning process in a generation”, but what will its legacy be? Amidst a period of uncertainty where our urban landscape is undergoing significant change, some of our most cherished buildings and spaces are under threat and our skyline is ever evolving, how sustainable is this model? And more importantly, how de we ensure these works remain relevant? Richard Wright sums it up perfectly when asked what success would look like for him: “slowing down time”.

COMPETITION

|

COMPETITION

|

COMPETITION

|

COMPETITION

|

COMPETITION

|

COMPETITION

|

COMPETITION

|

COMPETITION

|

NEWS

|

NEWS

|

NEWS

|

NEWS

|